- Degenerate Art

- Posts

- When bad things get worse

When bad things get worse

Border Patrol, ICE, and the repetition of grim history.

This week, we’ve learned that ICE leadership is being purged, allegedly by Department of Homeland Security secretary Kristi Noem’s special friend and employee Corey Lewandowski. We’ve already seen the footage of Immigration and Customs Enforcement leading violent raids across the country this year. Now, we learn that ICE will lose some of the key figures who’ve been leading these assaults. As Customs and Border Protection gets the upper hand over how the massive immigrant-persecution machine will operate in America, the shift will have big implications, which could be felt quickly.

This kind of internal conflict is one I’ve mentioned a few times in the last year. In rising authoritarian regimes, tension usually develops between the more law-and-order squads of the governing party’s goons—the ones who represent a more simple exacerbation of the existing awful system—and those who have embraced more radical forms of detention or extrajudicial violence. Think of it as a bad thing made deliberately, similarly worse versus potential fresh new hells.

It’s worth considering the coming shift from the ostensibly law-and-order version to the more extrajudicial model. I want to look at the echoes of these kinds of shifts in history, failures of imagination, and how to respond when things get worse.

Border Patrol Chief Gregory Bovino with a Third-Reich look (Photo: Mustafa Hussain)

ICE and CBP were established under the Department of Homeland Security in 2003, as part of government reorganization in the wake of the 9/11 attacks. They were largely split out of the U.S. Customs Service (along with the Immigration and Naturalization Service, whose responsibilities were given to CBP).

ICE includes ERO, which stands for Enforcement and Removal Operations. CBP operates in theory to protect the borders, though how that border gets defined and how deeply into the mainland CBP gets to operate might surprise you.

ICE currently has an acting director—Todd Lyons, who has been in that position since March of this year. ICE hasn’t had a director confirmed by the Senate in more than eight years.

Border Patrol has its own unsteady history. With 11 acting directors and only six Senate-appointed ones across its history, the agency has been managed by acting directors more than half its existence.

This is exactly the kind of wobbly leadership you don’t want for people with guns and an inability to play well with others. With its members famous for their abusive tactics, the Border Patrol union has backed Donald Trump since his emergence as a political candidate in the U.S and has been a steadfast supporter of anti-immigrant rhetoric and actions.

Old tactics for new times

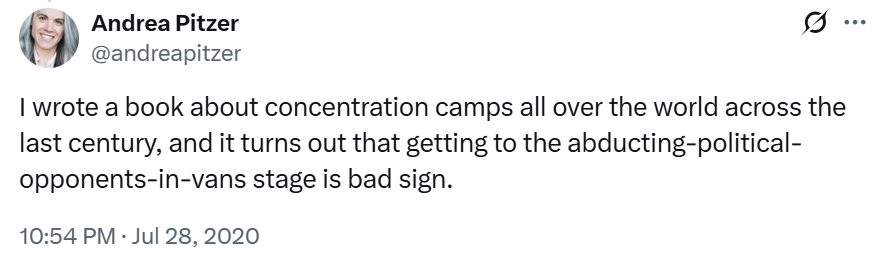

In 2020, agents of CBP’s BORTAC—the border patrol tactical unit—were dispatched to protests in Portland in the wake of George Floyd’s murder and the protests that followed. Some of you may remember the public horror back then in response to agents in unmarked vans kidnapping protesters off the streets.

For many outside immigrant communities, it was their first exposure to these tactics, which have been in use by police and various law enforcement agencies in cities for some time.

The deployment of Border Patrol agents also sometimes happened absent any invitation from—or even against the wishes of—local governments. These tactics foreshadowed how federal law enforcement resources and National Guard units are being deployed now.

Such actions rarely rise out of nowhere; their seeds tend to have been planted long before. What we’re seeing come to fruition now has been in process for years, for decades, and to a degree, for centuries. Our failures to stop these kinds of abuses in their early forms has allowed them to take root.

Anatomy of a shakeup-shakedown

The current purge of ICE is said to be in response to what the White House sees as low apprehension and deportation numbers compared to the quota of 3,000 per day set by Stephen Miller, the White House deputy chief of staff for policy. Recall that before the election, long before it became clear that Congress would cave entirely, Trump announced that he planned to deport as many as 20 million people, a number far larger than the population of undocumented immigrants in the United States.

“What did everyone think mass deportations meant?” said a Border Patrol officer to Fox News’ Bill Melugin. “Only the worst? Tom Homan has said it himself, anyone in the U.S. illegally is on the table.”

If Tom Homan won’t adopt the approach that DHS wants, the story seems to go, then Border Patrol is willing to take that challenge on themselves. They’ve already introduced a television-ready kind of showmanship seemingly designed to appeal to the president, jumping out of rental trucks like Patriot Front rejects who failed upward, or rappelling from Black Hawk helicopters onto the roof of a Chicago apartment building. In the process, they’ve done tremendous harm to immigrants and non-immigrants alike.

Foreseeing a tragedy

Before Trump took office again, I talked with Aaron Reichlin-Melnick, a senior fellow at the American Immigration Council, about the threat to immigrants that the coming administration would represent. He underlined the ways in which immigration had become a disaster across several decades because the government had effectively made it impossible for people to follow a legal track to citizenship.

When he considered the likely paths US immigration policy might follow once our already bad history was made worse by a president bent on punishing millions, he laid out two possibilities. One approach was represented by Stephen Miller and the other by Tom Homan.

He suggested that Homan, who had originally been appointed as ICE’s executive associate director of enforcement and removal operations more than a decade ago by Barack Obama, was a creature of the system. Miller, on the other hand, would introduce new tactics and methods less bound by any existing structure of detention and deportation.

What this would likely mean in practice was that if Homan gained the upper hand in immigration policy, he would more or less expand the existing U.S. immigration system, putting it on steroids. That system was already very cruel, with laws warped to allow widespread mistreatment of targeted groups. Under Homan, we should expect a massive increase in the kind of tactics that immigrants had suffered for years.

If Miller got control, however, he suggested that an already bad situation could change in significant ways. Miller’s crusade against immigrants risked becoming a much more dangerous project.

The Nazi example

I often try to use other examples than the Nazis in the detention history I share for this newsletter, because it’s important to understand how often and in how many places these dynamics have played out before. But in this case, I want to consider the Nazi case from the mid-1930s, beginning a year and a half after Hitler came to power. It’s a case that’s relevant for our moment.

Keep in mind that though the Nazis made aggressive use of preemptive, arbitrary detention from the first weeks of their rule, in the beginning, German concentration camps were largely like those in other places around the world.

In some cases, early labor camps were reminiscent of internment and labor camps for Ukrainians in Canada in World War I. In the worst settings, punitive early Nazi camps functioned more like Soviet pre-Gulag detention in the 1920s. There might be sadism and torture. Some executions took place. But in 1934, Nazi camps were not yet an anomaly in the world.

A purge in the summer of 1934, however, would help lead to a major shift. Beginning on the last day of June, the Night of Long Knives led to the elimination of Ernst Röhm, then the second most powerful man in Germany. His Brownshirts, the SA, had provided the street violence and enforcement necessary to power Hitler to victory. But now the party wanted something different.

Diverging paths

At that point, there were two visions of a German future. One focused on bringing the extrajudicial methods used to secure power completely under the control of existing institutions, since the Nazis had gained control over everything. After shattering their opposition in every direction (in some cases through murder), they could create a government relying on existing legal channels, rendered more aggressive and more brutal, but exercising power through the system they’d inherited.

The other vision was focused on maintaining a national state of ongoing terror. Mass detention through extrajudicial means—concentration camps—lay at the heart of that terror. Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler was its biggest proponent, and also the man who had the most to gain in terms of power from a massive expansion of camps.

I’ve found that there’s often this kind of inflection point in concentration camp history, where a system teeters for a time between abandoning extrajudicial methods or giving over entirely to them. While everything still lay in the balance, the German legal system tried to protect society from this kind of camp and the abuses that inevitably resulted. State prosecutors brought cases against camp guards, though Hitler stepped in to give pardons.

Meanwhile, briefly offering promise to the other possible outcome for Germany, in August 1934, Hitler did put limits on the uses of arbitrary detention (“protective custody”) ahead of an election in which he ran unopposed. He announced amnesties that freed thousands. Nazi leadership considered significantly reducing the role of concentration camps.

But Himmler ignored and worked against those who opposed the camps. He rearrested a thousand of the prisoners who’d just been freed. He ordered the arrests of thousands more of those he deemed suspect. He met with Hitler privately over letters of complaint and persuaded the Führer to take his side.

Himmler argued the critical nature of keeping terror constant and using camps to deal with the masses of internal enemies that remained in Germany. He wrote a letter to the minister of justice declaring that “the Führer has forbidden the consulting of lawyers and has charged me with informing you of his decision.”

So it was that the Himmler faction won out. In the months and years that followed, the Nazi concentration camp system devolved again and again into larger and more abominable forms—ones that would have been impossible to imagine in 1934.

The U.S. today

In our case, the diminishment of ICE’s authority and purges of its leadership are apparently meant to give Border Patrol agents free rein to use more extreme methods to increase the numbers of those apprehended and detained. The focus in prior administrations on people with criminal records, which had lingered in some corners of ICE, seems destined to be discarded completely in the pursuit of higher numbers.

In one way, this is the reverse of the situation in the Third Reich a year or two into gaining power, in which the street-violence methods of the SA were eliminated and brought under a more rigid Nazi hierarchy. In the case of the U.S. in 2025, the administration is loosing the violent cowboys of the Border Patrol on the country, moving immigration enforcement farther outside any rigid control at all. The federal government is fueling chaos.

Why would they do this? In part, as mentioned, because of the administration’s disappointment with the numbers of people ICE is detaining. I suspect it’s also because the White House hasn’t yet accomplished what the SA did for the Nazis early on. They functioned as a kind of internal unregulated army offering a level of street violence that cowed the opposition and made dissent a more fearful endeavor. In my opinion, expanding Border Patrol operations in cities are meant to intimidate and harm U.S. citizens alongside immigrants.

CBP has been known for open defiance for some time now. It’s likely no accident that U.S. Border Patrol Chief Gregory Bovino came to head up the operation in Chicago, or that he showed up in the city’s Little Village neighborhood in the days before the purge of ICE leadership was announced, with footage of him throwing what appeared to be a tear gas cannister at protesters.

He may or may not know German or Soviet history, but on some level, he seems to be aware of the role he’s playing. Hauled into court by U.S. District Judge Sara Ellis on Tuesday, he showed up in a long dark coat reminiscent of both Gestapo officers and Soviet Cheka officials.

The judge, too, seems to sense what is at stake in terms of history. Bovino’s appearance happened after she put a temporary restraining order in place October 9, blocking agents from using specific tactics on protesters. Video shows what overwhelmingly appears to be agents repeatedly violating the judge’s order.

Today, she announced that Bovino must be trained on the use of a body camera, and then wear it. She’s demanded that he show up each day to court for now, and that he will abide by the temporary restraining order. She’s trying to drag him back inside a legal framework of accountability.

Failure of imagination

To look at this from another angle for a moment, when I gave birth for the first time, I wound up with a kid who, for various reasons, couldn’t sleep when horizontal. I knew that newborns should be asleep the majority of each 24-hour period. But every time I laid the kid down, wails of distress followed.

In the end, my husband and I split the night, with one of us taking the baby from 11pm to 3am, and the other from 3 to 7am. It went on for more than a year.

We’d always planned that, if we decided to have any children, we would have two. But a year into parenthood, we had to have a talk about that plan. It had been a hard infancy for all three of us, even without any life-threatening medical crisis. Sleep remained an issue. There was no way we could repeat the last year again.

What were the odds, we asked ourselves, that a second kid would have the same issues? It had been so extreme, we decided it probably couldn’t get worse.

I got pregnant again, and again, was lucky enough to wind up with a healthy baby. But the second kid had even worse sleep issues than the first. It had been a failure of imagination to assume that something difficult was unlikely to happen again and get worse.

This kind of failure of imagination sometimes protects us. If we could imagine every impossible challenge or piece of bad news that lay ahead—especially without knowledge or guarantees of the good things that would also come—how would we ever get through life?

But our situation got so bad that we realized that we had to find help. When we did, it turned out that medical assistance was possible. What we needed to do was to switch doctors, and to change our whole strategy.

Six months into life with a second screaming baby, we found that a simple daily treatment made it possible for the second child to sleep, more or less, through the night. Our failure at the outset of parenthood to imagine that almost three years without sleep lay before us had given way to our failure to imagine there was any way out of it. But our worsened circumstances drove us to action anyway.

Don’t fall for it

My sense is that with Border Patrol taking the lead on U.S. immigration enforcement, we’re going to see a worsening of daily life for several parts of the country. Because of the administration’s targeting of people of color and its denigration of cities, these operations will take place mostly in urban areas to start.

Americans whose lives haven’t already been touched by agencies charged with immigration enforcement—even those historically worried about the effects of discrimination and police violence—have, in many cases, failed to imagine how bad things already were for those who had come in closer contact with law enforcement. And now the national failure to end the arbitrary violence sees it being visited on more and more people across the country.

I expect that the coming months will bring a rapid expansion of impromptu facilities, more porous categories for apprehension, and more aggressive tactics applied indiscriminately to those who stand up for the rights of anyone targeted.

Maybe you’ve seen this coming all along. But if you had a failure of imagination at the beginning—not knowing how bad it had already gotten or realizing how much worse it might get if we didn’t take action then—don’t let despair over how we got here paralyze you. Don’t let that first failure of imagination lead you into another one: one where you fail to imagine ways that we can get out of this.

Going forward now

The danger will increase this week, but the administration’s control isn’t locked in across the board nationwide. Everyday people still have so much power. When something bad happens, maybe even before it can, band together and plan together. Don’t forget you have resources. Use them.

My sense is that the administration has been overreaching consistently, and that this is yet another example. Compared to other countries where authoritarianism solidified, the federal government is rushing the persecuting-minorities side of its agenda before they have the kind of lock on suppressing dissent from the rest of the population usually seen in these situations.

Along with all the mutual aid projects—especially ones helping with food and shelter—one idea I’ve mentioned a few times is worth underlining here. Talking with people around the world about past camp systems and mass-detention projects, I’ve heard stories of how different sites were used. With Border Patrol taking the lead on enforcement, I think we’re going to see—along with massive facilities like Fort Bliss in Texas—many more ad hoc detention solutions. Expect use of the types of locations we’ve seen turned into improvised prisons in the past elsewhere: stadiums, schools, concert venues, civic centers, horseracing tracks, stables, hotels, motels, campgrounds, and even nightclubs and community centers.

In more recent decades, authoritarians seem to have made deliberate use of community venues beloved by the very people the government was targeting. So call or meet with your civic and community leaders, as well as your state representatives. Work on how to deny access to these venues for immigration enforcement operations in your area.

If your local representatives are currently supporting the administration’s policy on immigrants, then work with local businesses, developers, community groups, and religious leaders to create community pressure outside official channels. You don’t have to wait on politicians to lead the way.

But do campaign to elect people who represent your views locally, and to educate people about what’s happening. We are none of us helpless. But we have to act.

Your paid subscriptions support my work.

Reply