- Degenerate Art

- Posts

- Pity the person who needs something from me

Pity the person who needs something from me

A highly unlikely series of events, with receipts.

In recent weeks, I’ve often written about the expansion of US detention that repeats concentration camp history. The wave of violence is ongoing against immigrants, and more US citizens are being arrested in shocking ways. A new executive order seems set to expand abuses against the homeless. Colleges remain under attack—and media outlets, too. Many institutions people imagined as strong are caving.

People are looking for answers on what to do in the midst of all this. Next week, I’ll post a very nuts-and-bolts conversation with an activist on how to deal with ICE in your community, both in terms of watching for and responding to raids and also about how to get ICE out of your community as much as possible.

But this week, I want to offer a different response to those looking for answers. I have a strange and lovely story to tell you, one about the smallest of things—but about big things, too. This one will take a lot of turns then end with what I hope will be a useful way to approach responding to events in the U.S. and around the world today. This story has a true but almost unbelievable ending, and I hope you’ll stick around for it.

Life as a series of obligations

A lot of people have come to me with questions about camps lately. I started researching the larger history of concentration camps in 2008, and got my book contract for a global history of camps in at the end of 2014, which has meant more than a decade of pretty intense work on how parties or governments round up civilians and lock them away more for who they are than what they’ve done.

During the first Trump administration, the number of people in positions of power in the media who were willing or able to see how we were already even then transitioning to camps after decades of extrajudicial torture and cruelty—that number was small. Sometimes I would pitch an editor who would get it, then they would take the idea to their editors’ meeting, where it would be shot down.

At first, I just thought maybe I wasn’t pitching well. But then, with Trump administration abuses along the border becoming apparent in 2018, editors started reaching out to have me write something. Finally, I thought, people realize what’s happening. And some did. But in other cases, even when an editor had first reached out to me to solicit a pitch, they still ended up not able to sell the concept in their meeting.

Now, six months into a second Trump administration, both the president and Stephen Miller have openly talked for more than a year about wanting to detain and deport millions and millions of human beings. They now have whole law enforcement agencies willing to collaborate in these abuses, even when this occasionally means detaining American citizens or people with documents. The budget just approved for ICE will allow detention to expand exponentially beyond its current cruelties.

So many people are reaching out now, because—while there might still be some editors who are blind to what’s happening, or a much smaller number who want to deliberately misrepresent it—a lot of Americans can see what the plan is more clearly today than they could six or seven years ago.

Which means I’ve been getting a lot of requests for interviews, as well as private questions from people who have experience on campaigns or who’ve worked in politics, or even requests from community groups who want me to teach workshops on organizing for them. And sometimes the requests aren’t even for anything specific, they’re just a recognition that I can see a piece of what’s happening more clearly than some people could early on, or that I’ve already spent a lot of time thinking about what happens next when a country is in the situation we’re in. People want someone to do something—anything—to change what’s happening.

Your book is already doomed

This recent dynamic began to remind me of something from Twitter more than a decade ago. The platform was already kind of a pain in the ass by then but also often a lot of fun.

I followed a writer there named Brian Morton. He’s probably still best known for his novel Starting Out in the Evening, which was also made into a film. We never met in person, though we occasionally riffed on each other’s posts or exchanged asides in DMs. More often than not, we just hit “like” on each other’s literary jokes.

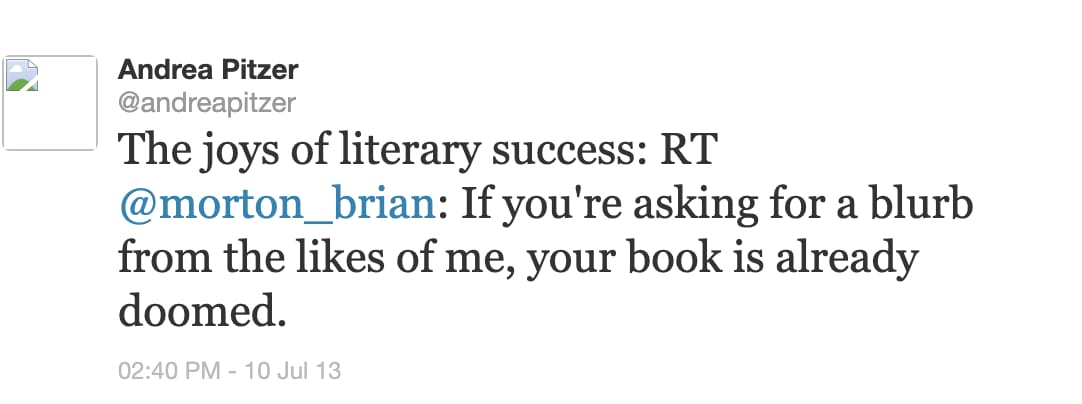

Around the time my first book came out, Brian posted that someone had asked him for a blurb. Without mentioning who had requested it, he wrote the following, which I reposted then. “If you’re asking for a blurb from the likes of me, your book is already doomed.”

The comment was very much in character, sharp-witted and administering small cuts that tended to target himself. The year was 2013, and I was an author who had gone blurb-begging for the first time earlier that year—but who had also only recently realized that having established authors say nice things about a book isn’t enough to land it on the bestseller list.

By that point I recognized the despair of both the author with the forthcoming book and the author willing to write a blurb but who knows their endorsement is unlikely to deliver the kind of sales punch that the requester is probably hoping for.

Brian’s words have stayed with me since, because as I’ve become a little better-known but still not a celebrity, I get a lot of requests for blurbs. I want to read the books before deciding and try to read as many as I can to help out other authors, just as I’ve been helped out. But Brian’s line is always in the back of my mind, especially with new authors, who might be imagining that a blurb from me is going to change the reception of their book or the trajectory of their career.

A homemade Newton’s cradle in motion (image from The K).

I’ve been thinking about his line again in a different way during the second Trump administration, now that so many people are asking me for help. And it’s not just me. People are looking for answers from anyone who seems to have a handle on events. Sometimes they look to those who are in charge, or to those who are speaking out about Trump and gaining an audience.

People want leaders. And it’s not so much that anyone who asks me for help is—to borrow Brian’s phrase—already doomed. It’s more that I know my skills and limitations. So for instance, the person who had a tremendous amount of community organizing experience and wanted to put it at my disposal for an unformed idea of a movement she thought I might lead had a certain idea of me—that I was someone she could follow who would save her or the country. And the group of people in one local community who wanted me to teach a workshop for them—they were recognizing that what I was saying was real, and they wanted me to tell them what to do next, to train them in what to do.

There was absolutely nothing wrong with people asking for things or offering to help. We have to reach out to each other. A real hunger exists to know exactly the right steps to take to fix our current disaster. Sometimes, someone will write me privately with an idea of how to collaborate, and I can instantly picture how we might work together or at least have a concept of how I might be useful that we can develop over time.

So this post isn’t a complaint about people asking for things. But sometimes I get the idea that people want someone outside their experience and their community in whom they can vest their hopes and power. But my sense is that there’s not one weird trick that’s going to do it, or one person who has all that knowledge, or a single leader we can elect who’s going to turn the tables. It’s going to take a million planned and improvised actions to shift what’s happening.

One of many reasons I quit teaching martial arts for a living after several years of doing so was because people were willing to vest so much authority in someone who wears a black belt. And credentials can be helpful in figuring out who to listen to. But I saw how much power people were willing to concede, how much faith they would have in their instructors, including me—but for what felt to me at times like not great reasons. It sometimes made me squirm.

Last week, I mentioned Brian Morton’s line about blurbs from a million years ago to my husband. After more than a decade in my head it had morphed into “Pity the person who wants a blurb from me.” I mentioned that what I was trying to say with my newsletter and podcast is that you don’t always need to look for someone who knows a lot more or who has more power to do the things that need to be done.

Nobody’s a superhero. Or rather, everyone’s a superhero, so really we’re just choosing our battle partners, forming our Justice Leagues.

On missing near-strangers

I’ve wandered pretty far from the blurb analogy here, because of course blurbs aren’t really a cry for help or a need to have the work approved of in a deep psychological way. They’re just part of the publishing business the way it’s done now. And people approaching me this year because of this podcast or because they connect to the things I’m saying in public about concentration camps is mostly a really good thing. But I still think of Brian’s line whenever I worry that people are wanting something from me that I can’t give them or that won’t be as transformative as they hope.

My husband suggested I write about this, using Brian’s original tweet to frame the post. But here’s the thing: Brian left Twitter during the first Trump administration. And when I went to look, his account had been deleted, too. His tweets are all gone.

During these intervening years, I’ve missed him in that strange way that happens when you feel connected to someone online, but having never met them in real life (or maybe even sometimes if you have), you don’t know if they have any sense of attachment to you. Fleeting contact on Twitter was the only way we had interacted.

I pondered reaching out to him at the college in New York where he teaches but thought maybe that was too strange—to write someone I’d never actually met and hadn’t interacted with on social media in seven or eight years about a casual comment they’d made in 2013, one I’ve invested with my own meaning since.

So I planned to write this post without referring to him by name. On July 22, I set up a draft entry as a placeholder in this newsletter so I wouldn’t forget. I used just a quick sketch of a draft title “I feel bad for the person who wants a blurb.” You can see the date I drafted it here.

I didn’t work more on the post at the time, because I’d gone away to the cabin of a friend who let me borrow it for a week to have a solo writing retreat. In theory, I was getting away from all these requests for interviews and opinion pieces on concentration camps that people want from me, and getting caught up on writing my next book, Snowblind, which I’m on deadline for.

But those requests kept coming even while I was at the cabin, because people very reasonably want information and answers about what’s happening. And honestly, as a journalist and author, writing and interviews are very much in my wheelhouse, and I want to be doing them. Still, I was trying to not agree to do anything else last week while I had this precious time to focus on my next book for sixteen or eighteen hours a day, which is how I work best.

Most of the requests that came in I got done before I left or put off until my return. But I did make one exception, agreeing to talk to Will Bunch at the Philadelphia Inquirer. Will and I have never met in real life either, but we post each other’s work sometime on social media.

The interruptions of pesky journalists

I talked to him in part because his column was going to come out before I got back from the cabin. And in a strange twist—bear with me here, I promise this will all come together at the end—I wanted to help Will out because he’d just helped me out in January.

I’d written him then about something that had happened back when I ran a record store in DC more than thirty years ago. Even though it was a fleeting connection, I’d always remembered the person involved. When I went to see what eventually happened to that person, I found out he’d died not long after I’d encountered him.

This person was someone society had forgotten about long before he died, but a Washington Post reporter did two stories on him in the 1990s that were heartfelt attempts to figure out what had happened.

That Post metro reporter from the 1990s went on to be Will Bunch’s boss today, the editor in chief of the Philadelphia Inquirer, Gabriel Escobar. So in the slow and weird way I have of gathering string on stories, sometimes across decades, I had asked Will Bunch for his boss’s contact info in January, so that I could reach out about this man who had died decades ago and see what his boss remembered. Will was kind enough to go the extra mile by introducing me and vouching for me.

I’ll tell you the story about that man who died another time. But for now, you might understand why I felt that I really ought to help Will out in return. So I agreed to talk to him that evening, but I bitched so much about how busy I was that he put it in the column, writing that I “was trying to finish an unrelated project, but kept getting interrupted by pesky journalists.”

After he interviewed me, I went back to work on my book. Will’s column went live last Thursday afternoon, July 24, under the headline “This column on concentration camps is the one I hoped I’d never write.”

The Morton in question

I went back to working on my book. But late that evening, I had to go into my newsletter database to look up someone’s account and fix something that had gotten messed up. And there, at the top of the list just before midnight on July 24, I saw an email address that had the name Morton in it. Here’s part of the info from his entry. (I’m keeping his email address private.)

Something else in the email address made me think it belonged to a New Yorker. It occurred to me that Brian Morton, whose long-ago tweet I wanted to write about this week, taught writing in New York. I sat and stared at the email address for a while, wondering.

On the off chance this might actually be Brian Morton appearing out of nowhere, it was such a strange and lovely development that it seemed impossible not to write this person to find out. I was a little worried that it might be the wrong person, and that I would unnecessarily alarm my new subscriber, some other hapless Morton who would feel I was accosting him and immediately understand any case of mistaken identity would be a disappointment to me.

But the next morning, I sent an email to the Morton in question anyway. Luckily for me and the imaginary Morton I’d invented in my mind, I found that Brian Morton instead, the one I was looking for. Or he had found me. Or we had accidentally found each other.

He replied on Friday, saying he hadn’t much regretted leaving social media, but there were some people he missed being in touch with, including me. We caught up a little. I knew that he’d published a book about his mother, Tasha: A Son’s Memoir, not long ago, and he told me he has another book, Writing as a Way of Life, coming in September.

I explained that I wanted to write a post and mention his blurb from so many years ago. I asked if he remembered the actual line he’d written at all. Perhaps he had exported his Twitter archive before deleting his account?

On Monday, he sent me a screen shot of not only the tweet, but also my reposting of it from 2013.

The whole situation seemed too improbable. What had made him think of me just as I was thinking of him, after barely knowing each other and not being in contact for several years?

He solved the mystery in an email, with an answer so obvious it should have occurred to me. He’d read Will Bunch’s column on concentration camps in that day’s Inquirer.

The magic at hand

Some people will tell you that they don’t believe in coincidences. I absolutely do. I think the world is full of strange wonderful moments, most of which we pass by without ever noticing.

I can be a real misanthrope at times, so I probably fail to notice the majority of those moments myself. What’s more, I deeply feel the burden of requests that I don’t have time to answer, or that are for things I’m unlikely to be incapable of providing to people who are desperately seeking help.

At the same time, I do also believe that we’re going to need to find solutions not alone but together, in concert with other people. The path for getting to them isn’t going to be conveniently organized under the banner of a leader whose direction we follow or a person who has all the answers.

I’m thinking of the woman who’s become known as the Lululemon Lady yelling at ICE and shaming them for not letting her get a phone number from an immigrant they’re taking away. (She wanted to call his family to tell them he’d been detained.) I’m thinking of the lawyer who was on the scene filming that interaction, and how those two people were both critical to the world learning about this story.

I’m thinking of the L.A. neighborhood that turned out to tell ICE to fuck off. I’m thinking of the Massachusetts town of Milford that came together to protect eighteen-year-old immigrant Marcelo Gomes da Silva, a beloved high-school kid who was detained by ICE.

I’m not saying that these people’s responses to their local situations are what everyone should do all the time. Next week, I’ll come back with a post about a coherent approach shared by an actual organizer (not me!) for you, to help you think about actions to take in your neighborhood.

What I want you to remember today is that we’re all finding our own way through the darkness. And a lot of us, I think, are prone to imagining everyone else as in much better shape than we are—maybe they’re wealthier, have more influence, or are happier. Maybe they eat only nutritious foods and can more easily weather the current tragedies.

While it’s a great idea to reach out to people you think might have answers or ideas for you, don’t wait for the perfect plan, or to be anointed. Don’t wait to be led. You can also connect with people near you, even just a couple friends, and do something locally that meets a need where you are, right now, today.

We each have our own world in which we’re thinking of one another and changing lives in ways we can’t predict and may never know about. You might remember someone from years ago and recall something they said that affected you. Maybe you’re being an ass to someone who’s reached out to you for help, emphasizing exactly how very busy you are.

But you help him out anyway, because it’s an hour of your time, and who are you, Jesus? Besides, he’s doing something good. And anyway, he’d helped you out not long ago, too.

And you doing that might deliver to your doorstep the next day the very person you had wanted to talk to, all by chance, even though that person had disappeared from your life years ago.

So many bad things are happening. So many new surprises drop like bombs every day. But by reaching out and by responding to one another, some of those surprises will be good ones.

Making our way with tools already within our grasp in the company of those around us—people currently in our lives or part of our community—is our best bet for shifting everything that’s happening now. Of course there’s hard work involved, too. But so much of the time we already have the means at hand to do magic. Don’t wait to notice it; don’t forget to embrace it.

Your paid subscriptions support my work.

Reply