- Degenerate Art

- Posts

- August 22 Friday post

August 22 Friday post

The Undead, childhood, and the vast strange horizons of art.

It’s been a while since I posted a story from my childhood. That’s partly because so much is going on in the world, it usually feels more important to be addressing current events right now. Another reason is that since my childhood was both harsh and prefigured what’s happening in the U.S. at the moment, I don’t want to dredge any more layers of misery into a moment in which people are already struggling.

But the truth is that there were also a lot of strange and lovely moments in how I grew up. Today, I’ll tell you about the first novel for adults I read. I was in elementary school, and page after page of it still sings in my imagination and memory—not because it became my favorite book, but because it was so new and different than anything I had read. It opened new vistas.

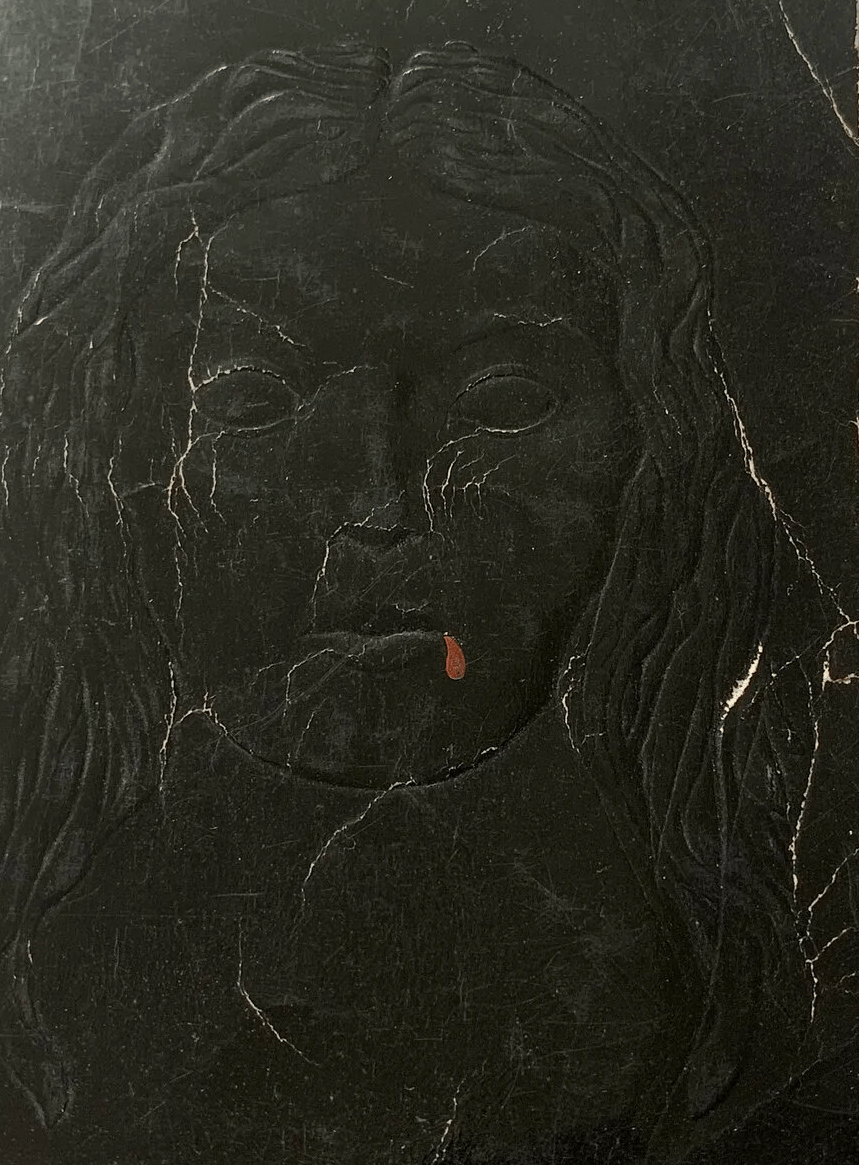

The cover of the 1976 paperback edition of ‘Salem’s Lot.

In 1975, my mother left her job as a hospital social worker and went to work for Easter Seals. After school, I sometimes went with her to the office. Playing in the therapy room, I met children with cerebral palsy, multiple sclerosis, speech impediments, or prosthetic legs—children who staggered or sat lame in the sight of God, like tiny versions of my great-grandfather, who had to learn to walk all over again after doctors amputated his leg. There were so many of them, from toddlers to teenagers. I wondered where they had come from and why I’d never noticed them before.

My mother bloomed there. She knew how to fundraise and organize events. She could elicit from others a kind of faith in her—a faith I myself still had—to make a bad situation better. Promoted from public relations to deputy director, she began going to conferences with other Easter Seals administrators.

The first time she left for a conference on a Friday, her absence made me nervous. I didn’t know what my stepfather would do if he could be sure she’d be gone all day. I packed snacks and stayed outside as much as possible, beyond calling distance from our old Victorian house.

She returned home that Sunday, looking exhausted. Unpacking a small suitcase upstairs in her room, she fished out a book, a paperback with a black void for a cover. I could see no author or title. She threw it on the bed.

“I borrowed it from someone who didn’t want it back,” she said.

She’d read it in her hotel room, staying awake half the night to finish. Once she finished, she couldn’t fall asleep.

Passing my fingertips over the dark void of the cover revealed a design. Held at a different angle, ridges caught the light and formed a death mask of a girl. The only visible color was a thin drop of blood at one corner of her mouth.

I was infinitely susceptible to that cover. The title on the spine read ’Salem’s Lot in fat, elegant letters. I ran off with it and began reading. A writer named Ben met a woman named Susan in a small town where people started disappearing. They wondered if a vampire had moved into an old house on a hill overlooking the town—a house not unlike ours.

Susan sneaked into the house to kill the vampire. She got caught and turned into the creature on the cover of the book with the bloody mouth. People in the town couldn’t see what was happening or didn’t want to.

In the same evil house, a man had shot his wife then hung himself upstairs. Someone else got strung up from the rafters in the same room, gutted and drained of blood. Elsewhere, an exhausted mother beat her baby. A doctor was impaled on knives; a priest lost his faith and became unclean; there was nakedness and adultery. I was eight years old. It was the first novel for adults I’d read.

Like my mother, I could hardly sleep. When I finally did, I dreamed I was walking down the upstairs hallway in the house on the hill at night. I went into the bathroom, and in strange logic of dreams, the light switch was inside the linen closet on my left.

As I reached for the switch, I noticed that the closet was bigger than I’d thought. Then, in the still-darkness, I sensed that directly under the switch lay not a shelf but an abyss, the opposite of glittering, in the shape of a coffin. The smell—how had I not noticed it from the hallway? Dread swallowed me, and I froze with my hand extended, in terror of waking the vampire I realized was sleeping there.

As soon as I could move again, I pulled my hand back. I did it so quickly, I hit myself in the face and woke up in bed.

I didn’t ask myself why a hungry vampire would stay in his coffin asleep in the middle of the night, or why he would haunt our bathroom in West Virginia, as if he’d been informed I’d just finished reading a novel about him. Instead, the dream unsettled me. I couldn’t filter anything out; everything I read went directly to my core and lodged there. The writer, the child, the undead girl, even the vampire—all of them had become part of me. Now I was all of them, too.

Each half of ’Salem’s Lot had epigraphs; their strange language caught and pinned me. On the first page of the novel, a quote from Shirley Jackson described a house that was not sane. I understood what she meant but stopped to wonder over how she said it.

The second half of the book opened with a poem, “The Emperor of Ice Cream” by Wallace Stevens. It wasn’t like the poetry I knew. Some lines rhymed; others didn’t. Even after a character in the novel explained that the woman in the poem was dead, there were phrases that left me confused. A dresser in the poem was “lacking the three glass knobs.” I immediately visualized the knobs, faceted and reflecting light, with their bolts protruding—which was the opposite of them being lost. Why did the poet summon the knobs in the poem by saying that they weren’t even there?

This wasn’t the same as reading to discover what would happen next. I went back and reread the epigraphs to find out what had already happened, to understand what I’d missed. Words were alive and could have more than one meaning. They might trick you.

In my mind, it all had something to do with the copy of R. Buckminster Fuller’s Synergetics that I’d checked out of the library the year before, puzzling over its diagram of two triangles bent into different shapes. One plus one could equal four. These thoughts set my fevered brain in motion.

A figure from R. Buckminster Fuller’s 1975 book Synergetics.

The next time I went to the county library, I was standing in adult fiction looking at the wall display of new books. One paperback cover showed a pair of gloves and a top hat—all white—sitting on a lace tablecloth with a cream-colored walking stick and photograph of a girl. A cherry-red switchblade script announced the title: Interview with the Vampire.

The librarian who discouraged children visiting her section was away from her desk. I took the book from the display and put it inside my jacket. She returned and saw me as I headed for the stairs. Though she had come after me other times in a huff, that day she only half-heartedly gave chase to shoo me away. I knew that if I made it to the upstairs checkout counter, Anne, the head librarian, would let me take home anything I wanted.

This novel didn’t unfold in a small town. It began in New Orleans and made its way to Paris, where a group of vampires ran a theater and lived together. The story was a romance, like the books my grandmother read, but between men who were vampires. In it, a child also became a vampire, who then tried over and over to kill the one who had made her into a monster. Like ’Salem’s Lot, it gave me nightmares, but ones in which the living room of our old frame house had transformed into a theater that was home to a nest of murderous undead.

Nevertheless, after that I devoured every horror story I could find, from Edgar Allan Poe and Bram Stoker to H.P. Lovecraft. As the options for classics grew fewer, I found myself reading The Amityville Horror and The Omen. In time, I was scraping the bottom with Moonchild, about a child freak born on the last day of February during a special leap year. The boy died young then emerged from his coffin to rip out his victims’ throats with one overgrown arm.

The same year, my grandmother gave me an advance reading copy of The Legacy, a supernatural murder mystery that had been adapted from a recent movie. Though I wasn’t allowed to watch the screen version, I consumed the book in one afternoon, rattled by the passage in which a woman drowned as the surface of the pool she was swimming in suddenly, demonically solidified.

More Stephen King books arrived before I finished elementary school: The Stand, Night Shift, and The Shining. The language in them never riveted me the way Shirley Jackson or Wallace Stevens had in ’Salem’s Lot. But every now and then, a phrase like “groping for purchase” would startle me. Similar phrasing appeared in his other books, too, and I understood that those words meant something to him. I began to think about the mind of the writer at work behind the story, fixated on its own ideas over time.

More often, the person I saw reflected in the books was myself. “There’s something in you that’s like biting on tinfoil,” one character in The Stand said to another, and I thought, Yes, I’m like that, too.

***

That New Year’s Eve, my mother and stepfather went to a party and left my brother and me at home alone to celebrate. I ate donuts and watched old movies on a small UHF station broadcasting from somewhere deep in West Virginia.

The first one showed Marilyn Monroe in a fever dream I couldn’t quite follow—a torrent of glowing colors that left her strangled by her husband at Niagara Falls. Next came Frankenstein, in which the scientist was terrifying, and the creature seemed doomed from the beginning. I thought it would be like the horror novels I’d read, but it was instead achingly sad.

After the monster had been burned alive and the credits had run, I sat alone in the dark in the living room, my brother having disappeared hours ago. Midnight had passed and gone entirely unnoticed by me, while the frozen ground sighed through the floorboards over the crawl space beneath my feet.

The broadcast seemed to end. But then the station began to play a silent movie of a rose. Seeing it just after Frankenstein surely shaped my sense of its meaning forever, but like Shirley Jackson and Wallace Stevens, the film felt alien and beautiful.

In a waltz of lapsed time, the petals twitched, quivering from bud to blossom then full bloom. After twisting fully open, they turned back on themselves or fell away, dying just before the picture cut to snow and static. I woke later on the couch alone, the TV still on, doomed to my ecstatic experience with no words for what had happened or anyone I could say them to.

Your paid subscriptions support my work.

Reply